Stick a bunch of humans in a room and what happens? Brilliant innovation? Or the next world war?

Anytime you gather humans together, there is friction. Some of it is good, a lot of it is bad, but it all comes down to the level of trust we build. And it turns out the trust is not just a feeling; it happens on the chemical level as well. The neuro-chemicals in our brain are released when we work in a high-trust environment that enables us to be more productive and work well with others. So, how do you create that? Start the injections?

Dr. Paul Zak has all the answers.

What we learned from this episode

Individuals who work in high trust organizations are more productive and satisfied with their jobs. They get sick less and they turn over their jobs less frequently.

Any positive social interaction you have will cause your brain to make oxytocin at least for a couple of seconds. By capturing these changes, we can measure how our physiological stress changes and motivates social interaction.

There’s an intermediate level of stress called challenge stress where people are the most productive. When people are given concrete stretch goals that they can do, they draw on the people around them to get those tasks done.

What you can do right now

If you find an overworked employee, tell them it’s important to be well rested, see their family, and get some sleep so they can come back the next day, energized.

If you have a new team that doesn’t know each other, make sure everyone has a voice, everyone feels respected, everyone feels cared for.

Key quotes

“There’s no underlying dialogue in the unconscious that you can tap into. You can fake it, and little bits leak out here and there. But it’s like asking your liver how much it’s enjoying processing lunch you just had. It’s just not a meaningful question.”

“We talk a lot about culture being important but culture is such a big, giant word. It’s hard to know what to do with that.”

“So, almost everything in biology has an inverted U curve. If I have too little stress or too little provocation to engage with people, I’m just going to be a couch potato and watch TV all day. If I have too much stress, I go on survival mode. I’m not a good social partner. I’m not a good teammate. So, we want to put people in this intermediate range that we call challenge stress.”

Links mentioned

Trust Factor: The Science of Creating High-Performance Companies

The Moral Molecule: The Source of Love and Prosperity

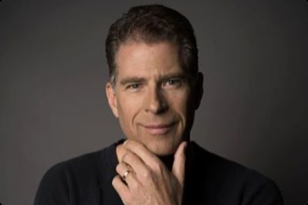

Today, our guest is Dr. Paul Zak. He’s a scientist, author, and speaker. And this is Work Minus Friction. Hi, Paul. How are you?

I’m great, Neil. Great to talk to you.

It’s going to be really exciting to talk to you, too. I’m excited about this podcast because you come with a lot of different experiences and a lot of exposure in different worlds. But you have a very fondness for the business world and how that can be improved. So, why don’t you start off just telling us about yourself and your career?

I’m a professor at Claremont Graduate University of Southern California. And I’m a fourth time entrepreneur in the startup world. So, basically, I’m a tool guy. I help create some of these interdisciplinary fields, including neuroeconomics, neuromanagement, neuromarketing, using what we discovered experiments in our science to solve business relevant problems. And I love building tools, software technology. So, that’s my little niche that I’m in.

What is it that you’re in right now in terms of neuro plus what? What’s your latest thing you’re looking at?

We’re really looking at how to measure and create extraordinary experiences. So, you don’t want to marry a so-so lady, you don’t want to go to a crappy movie, and you don’t want to be taught by a professor who’s boring. So, how do we know that? Now, you go to some off site, and they give you a survey when you get home. Or I fly a lot. I fly United Airlines as so United sends me a survey, hey, tell us about your trip. Well, gosh, I got that two days after the trip, I can hardly remember where I was coming from, honestly. So, what we have developed is a wearable technology and cloud based servers that allow us to measure second by second for a room full of people at a concert, at an off site, at your workplace, how much you value the experience that you’re engaged in. So, that could be a movie, it could be a TV commercial, it could be the work you’re doing right now. And once we can actually identify subjective value, then we can go back and reverse engineer that process and create extraordinary experiences.

Sounds like you have your biological feedback in addition to your subjective feedback.

Yeah, I mean, our conscious brain is maybe 1% of what our brain is doing. And yet, somehow, we think that because our brain creates language that we have any insight into our unconscious processes, and we just don’t. I think we had this Freudian hangover that if we just dig hard enough, that deep well of the unconscious will become conscious. But the data streams are completely different. There’s no underlying dialogue in the unconscious that you can tap into. You can fake it, and little bits leak out here and there. But it’s like asking your liver how much it’s enjoying processing lunch you just had. It’s just not a meaningful question. But we have technologies now, and particularly with the computing power we have in the cloud, that allow us to measure unconscious emotional experiences in real time and at scale. And that’s really brand new. So, that’s 20 years of my life. So, it’s a tool, and once you have a tool, then we try to make it available so that people can use that tool to solve hard problems. Like, why does work sometimes suck?

Let’s get into that. We’re calling this episode Work Minus Friction. So, where do you see friction in the workplace based on your experience?

There’s friction between humans wherever we go. So, the really interesting thing about humans to me is that we’re gregariously social. We like being around other humans. It’s fun to live in big cities, New York, LA, Chicago. But if we live in those big cities, we’re going to run into some weird people, or maybe we’re the weird people that people are running into. So, there’s always going to be friction with a social creature, intentional or unintentional. At work, one of these really interesting thing about humans is you can take these unrelated individuals, put them in a big building, and have them work together for joint projects to affect the goals of the organization. So, to do that requires very specific evolved brain structures, in particular the use of a neurochemical that my lab first developed a tool to measure about 20 years ago called oxytocin. And oxytocin is this key signaling molecule that tells me that, Neil, wonderful person, want to be around him, and your assistant, Steffi, what a weirdo, I’m going to stay away from her. So, it doesn’t have to be perfect. It just has to be good enough. And so we begin studying oxytocin. First, clinically, like, why the heck are we so social? Why do some people fail at that? And then begin to apply this to the workplace. And we discovered that individuals who work in high trust organizations are more productive or satisfied with their jobs, they get sick less, they turn over their jobs less frequently, multiple measures of business relevant outcomes and employee relevant outcomes are better when you live in a high trust workplace. And the question is how do I create that.

So, first off, I think you’re the first person who’s ever said that they like me more than Steffi. So, that’s interesting. But second, without getting too scientific on us, I’m really interested to know how you actually measure the oxytocin.

Good question. So, this technology developed in the early 2000s… So, oxytocin is this little molecule made in the brain and on stimulus you can get to be released in the brain and in the bloodstream. Why is that? Because it’s a super weird evolutionarily old molecule that dates back to fish at least 400 million years ago. So, it’s just this funky little system where most other chemicals that are active in the brain are not released in the blood supply. So, because of this work, if we do very rapid blood draws, because it has a short half life, and then treat it in a special way, we can capture the change in blood, which reflects the change in brain. So, that’s a long way of saying before and after blood draws was the technology we have developed from 2000 until about five years ago. And then we spent so much time chasing out the pathways where the receptors for oxytocin live in the brain and in the peripheral nervous system outside the brain in the body, that we were able to show that the receptors of the nerves that control the heart also have receptors for oxytocin. And we can capture that effect by using electrocardiogram. So, it’s not heart rate. But it’s the variation in beat to beat intervals that oxytocin affects. And this was known before my work. What we did was we wrote a bunch of algorithms that made us able to measure that in real time. So, now, I can measure this interaction in real time or this effect in real time. And I guess the punch line here, Neil, is that just about any positive social interaction you have will cause your brain to make oxytocin at least for a couple of seconds and we can capture those effects. So, that may be when you walk in the door and your daughter runs in your arms and says, “Hi, daddy!” It’s petting a dog. It’s having a nice meal, a glass of wine, sitting in a hot tub. So, all these things increase the opportunity for the brain to make this little neurochemical that reduces our physiologic stress and motivates social interactions.

So, if I give you a team that is experiencing a lot of negative friction, that is not getting along, nothing’s really coming out of it, they’re unproductive, what do you expect to see on a chemical level? What’s going on?

So, we see high levels of stress. By the way, I should tell you, besides running experiments in laboratory, we’ve run experiments in for profit businesses, and a bunch of those in my book “Trust Factor“, allowed us to present their data. So, Herman Miller, Zappos, lots of other places that allowed us to come in, actually take blood from their employees, measure brain activity, measure productivity. So, we find these individuals who are in these very stressful, high friction workplaces, is that people, not surprisingly, have high levels of stress and are radically underproductive relative to people who are less stressed out. They’re also less innovative, and they get sick more often. So, they’re in this unhappy place.

And then how does that compare with teams that are productive? Is it really that oxytocin is elevated in those teams?

Yes, that’s correct. Not only is oxytocin higher in high trust teams, but a couple other interesting things happen. One is that when we run studies measuring innovation, these high trust teams innovate more effectively than low trust teams, these high trust teams feel closer to their colleagues so they’re more effective team members. And then perhaps most interestingly, they shed the stress at work more rapidly when that team separates. So, they come together, they are focused, they have high physiological arousal, but they’re relaxed enough they can innovate. And then when work is over, boom, they’re back down to baseline physiology. And they’re not carrying that chronic stress around with them, which obviously is bad for your health.

So, you dropped the term on us called a high trust team. How important and how central is trust to this whole equation?

I think it’s exactly central. We talk a lot about culture being important but culture is such a big, giant word. It’s hard to know what to do with that. But we’ve shown, again, over 20 years, that a culture of high trust effectively improves performance, multiply measured, some of the measures I just talked about. So, trust really seems to be the key and because we know about the physiology of trust, driven by oxytocin, then again, we can create tools to reverse engineer that. So, in one of my startups, we created a survey and interventions for companies to use to measure and manage their cultures for high trust and high performance.

So, when I think about trust, one thing I always think about is the fact that there’s many different ways to build trust. Some people really like it when others follow through on their work. Others like it when somebody will ask personal questions about their life and show interest in that. So, are there universal ways to build trust or does it depend on the individual?

I think the answer is yes and no. I mean, having done this for a long time, have tried and true ways that we know build trust between individuals and build trust within organizations. How you apply those, the nuances of that, are quite different. So, right before I spoke to you, I spent an hour on the phone with a very large Brazilian company in which trust is one of their core principles. And it’s been falling for a number of years as they’ve grown. And so, they want me to come down there and give them a trust pickup. And so, we’re going to collect data, we’re going to sit with the executive team and develop strategies to intentionally build trust between team members, and thereby raise their performance.

And do you find that when you do those things, especially across cultures, like you’re talking about, is it the same in the U.S. as in Brazil, as in China, as in India in these situations, or do you have to adapt?

That’s a nice thing about starting with neuroscience. Brains, across all individuals, roughly work the same. So, absent psychopaths who we’ve actually studied, everybody else pretty much has an intact oxytocin system. So, if we start from the neuroscience, we have confidence that the kinds of interventions we’re creating are going to work for most people. Again, the specific cultural interventions is a function of the leadership, the history of that organization. I can’t start from scratch and go, hey, go from A to Z, you’re going to have to go to A to B to C. You’ve got to take some steps to get to where you want to go. And that’s why you need the executive team to be part of this process, not just having me drop in some general rule.

We started off saying we’re talking about Work Minus Friction, but there’s some good side to friction, at least good side to good stress you talked about. So, what is that good side to having a little bit of newness or stress in a situation?

So, here’s the most useful thing probably I’ll say for the whole podcast. It turns out that the human brain is a super lazy organ in the sense that it takes 20% of our caloric intake to run your brain. And because the overhead is so high, your brain wants to idle most of the time. So, almost everything in biology has an inverted U curve. If I have too little stress or too little provocation to engage with people, I’m just going to be a couch potato and watch TV all day. If I have too much stress, I go on survival mode. I’m not a good social partner. I’m not a good teammate. So, we want to put people in this intermediate range that we call challenge stress. I want to give people concrete stretch goals that they can do, particularly draw on the social resources around them, the people around them, to accomplish those goals. And then you get high levels of oxytocin release, you also get this shedding of stress, as I mentioned earlier, after the work is over. So, it’s really a challenge, and then relax, challenge, relax.

So, we want to put people in that middle range. So, how do you know if people are in the middle range? That’s where I think having people skills, people call it soft skills, but they’re really the hard skills, reading people, looking for people working too many hours. So, Boston Consulting Group has something they call the red card, if you work two weeks in a row, 60 hours or more, you get a red card. And then on the next Monday, your manager talks to you and says, hey, Neil, this is not sustainable. We know sometimes we have deadlines. We’ve got to work overtime, but we’re going to need to shed some of your work because we can’t have you working this much. It’s not that we don’t want to bill the clients for your time. It’s that we want to have a long-term relationship with you. We want to make sure that you can go home, get some sleep, see your family. All those things are important. And so, I think we should do the same thing. So, companies that practice the type 40, want to see the parking lot empty at 5:15, have you go home, relax, get enough sleep, see your family, and then come back the next morning, energized at 8:00 am ready to go.

So, Paul, I’m going to throw an idea past you. On previous episodes, we’ve talked about diversity and inclusion and the importance of that. And we’ve talked about studies where teams that are homogenous tend to not perform as well as teams that are diverse. And one theory behind that is that teams that are homogenous almost trust each other too much, at least they’re too comfortable with each other, and so, they don’t really challenge each other, they don’t expect things. Whereas a more diverse team, you’re going to have to come in with a little bit of stress about you. Do you feel like that’s accurate from a physiological standpoint of what’s going on?

I mean, surely a lot of evidence in the organizational psychology literature showing that diverse teams, again, diversity, multiply measured, gender, ethnicity, background, training are, in fact, more productive and more innovative. From a physiologic perspective, you’re always balancing this comfortableness around people that look like me, talk like me, versus people who are different than me. And this is where I think trust comes in. Diversity only works when you have this underlying connection between individuals. And so, an easy way to do that is to spend the first hour, depends on the team, just getting to know each other. So, we’ve got a new team, we want to make sure everyone has a voice, everyone feels respected, everyone feels cared for. Tell us something about yourself. Tell us why you’re here. Tell us why you love doing this or tell us what drives you nuts. Reveal some personal information, be vulnerable, you start to build those ties. So, before you throw a team together, you’ve got to actually design the structure so people can actually figure out how to work together and still have dissenting views so that we get to better result, but do that in a respectful way.

So, for example, the average time a team is together at Google is three weeks. Three weeks, right? So, they’ve got to pretty quickly figure out how to work together. And the first thing they do is sit down and talk about themselves, not just their professional background, but their personal background. Why did you come to Google? Where did you go to school? Why is it so weird to ride these bikes across the Google campus? Whatever it is. So, when I do this, just as an idea for the listeners, I always try to have people tell me something weird about themselves. And I do the same thing for me. So, tell me something weird about yourself that people don’t generally know. So, I had one guy say, I can’t make this stuff up, right? I can just remember it. I had one guy say, “I have the biggest big toes.” I’m like, okay, we gotta see that. Can you take your shoes off? The guy took his shoes off. He had giant toes. They were enormous. I had another lady say, who was, I don’t know, say late 20s, she had never flown on an airplane. And I’m, like, oh, my God, how is that possible? Like, you have a real job, you’ve never flown on an airplane? Are you afraid to fly? She said, “No, just never had a reason to.” That seems so odd to me. So, anyway, you can break down those normal barriers we have against letting people in and getting to know them and building a relationship with them if we do something that’s a little vulnerable, or weird, or unusual.

Let’s take it to the team leader aspect, the manager aspect. How much of management is art and how much of it is science in terms of what you can measure? And what is the real human aspect that managers should be bringing to their roles?

I think it’s both an art and a science. And I think what managers bring to that is humanity. A couple things, one that I talk about in the book, everyone that works is a volunteer. They’ve chosen to work here. Not for you, but with you. If they have any skills at all, which is everybody, they can go somewhere else. So, number one, treat them like a volunteer. That means, at a minimum, say please and thank you, at a minimum. So, I’ve got to treat them properly. And to do that means I’ve got to be caring, I’ve got to be respectful, I’ve got to be honest and transparent. And in doing those things, I will build trust with them. So, it also means that I’ve got to model this. I can’t pretend like I’m a God just because I’m in charge and there’s some physiological reasons why we begin to behave that way, which we could talk about. So, you’ve got to suppress that instinct to think you know everything or you’re in charge of people’s lives. These are adults. They can go elsewhere. And they can give you lots of discretionary effort or they can do the minimum. And a lot of that is up to the leadership.

Paul, it’s been really interesting to talk about the physiological part of it. We don’t talk about it enough, the fact that what we’re doing is on a chemical level, what’s going on, how we’re building trust, how we’re connecting to the people. For people looking for more about your books, obviously you have “Trust Factor“, what else do you have out there for people in terms of resources?

“The Moral Molecule“. You can do a trust survey at ofactor.com. That’s free. Find out more about measuring neurologic activity scale at immersionneuro.com and more about me at pauljzak.com. That’s a lot of websites.

That is. You’re quite prolific, man. You got a lot going on.

I don’t have a life.

Well, Paul, thanks so much for being on the show. We appreciate it. And thanks for coming in and sharing your insights.

Thanks, Neil.

Paul Zak is the founding Director of the Center for Neuroeconomics Studies and Professor of Economics, Psychology and Management at Claremont Graduate University. He has degrees in mathematics and economics from San Diego State University, a Ph.D. in economics from University of Pennsylvania, and post-doctoral training in neuroimaging from Harvard. You can check out his academic lab, consumer neuroscience company, and neuromanagement company. He also serves as a senior advisor to Finsbury, a global leader in strategic communications that advises many of the world’s most successful companies.

Paul’s research on oxytocin and relationships has earned him the nickname “Dr. Love.” That’s cool. He’s all about adding more love to the world.