Mark Crowley built his career on treating people well, recognizing their humanity, and addressing their needs as people. And he did that all in the cut-throat financial services industry.

When he had finished a book on his approach to employee well-being, he took a big risk. His publisher wanted to call his book “Killer Engagement”. He wanted to call it “Lead from the Heart”. Sexist overtones aside, Mark couldn’t stand down because he knew that it is addressing the emotional side of people that leads to the most true employee engagement.

In this episode, Mark goes deep into what it means to be more compassionate to the people we lead, and what it takes to be a truly great holistic leader of humans, not just results.

What we learned from this episode

-If you are managing with fear, you are threatening people’s security, one of the most basic needs.

-Only 3 in 10 people have a natural inclination to see other people do well. If you aren’t one of them, you either need to build it, or look for more individual contributor roles.

-You rarely regret being compassionate.

-Millennials aren’t disloyal; they changed the rules on what kind of loyalty to expect from an employer.

-Why Bruce Bochey might be the best manager in the history of baseball, but the Padres fired him anyway.

What you can do right now

-Get to know the people on your team individually.

-Find ways to encourage them personally and recognize them as a person.

Key quotes

“When people have that steady diet of positive emotions, you put them into their optimal level of performance.”

“But it requires that it be authentic. You can’t fake this. You have to really love people. And you have to want to see people thrive. You can’t compete with your people. You can’t be threatened by your people. So, it takes a certain mindset. But if you can operate this way and manage people this way, the rewards are just extraordinary.”

Today, our guest is Mark Crowley. He is an author and leadership speaker. And today we’re talking about Work Minus Ignoring Employee Well Being Hi, Mark. How are you?

I’m great, Neil. How are you?

I’m doing really good. I’m excited to talk to you because we’re talking about a topic that’s really important to people who are out there leading teams on the front lines. It’s about thinking about the people that you’re surrounded with, the people that are reporting to you, the people that are a part of your team. So, this is a really important topic. I want you to start, just give me a little introduction about who you are and how you got into this business.

That’s such a big question.

Just maybe 10 words or less, right?

Well, okay, I will tell you that I had a 20-plus year career as a senior leader in financial services. And after being named leader of the year for that organization, I left and I wrote a book. And in the process of writing a book, honestly, Neil, I came to realize that I was put on earth to say something really important about how we manage people and really to pin it down to say that the way we’ve traditionally led and managed people and the way we continue to teach people how to manage and lead is not only destructive, but counterproductive. And very much what I’ve learned is that everything we’ve thought was weak and soft about leadership tends to be the thing that drives the greatest performance.

So, we’re going to get into that. I want to first ask you what made you decide to leave the organization you were at after you looked like you’re retiring when you hit the top. You have this team, you are the best leader, you write a book. And then it’s like you feel like you’re going to reach more people if you do this speaker-author route. What was your thought?

So, there was a lot of synchronicities that happened through the whole process. And one of them was the nudge that I got to leave financial services. So, my last position, I was running sales. So, I was the national sales manager for financial services, investments, insurance products, for about 4,000 branches across the United States. And in my first year, we had record revenue, record profit, I was named leader of the year, and not that long after, the organization itself failed and was sold to another organization. And I don’t mind telling you that it was Chase that it was sold to. And so, obviously, the role that I had was eliminated immediately because the acquirer had somebody in that position. But I stayed for six months. And I was just repelled by it, instinctively knew that I wasn’t going to be a fit there based on how they treated people. So, I ended up leaving and had the thought of what am I going to do now. And maybe this would be a great opportunity to fulfill more of a bucket list ambition that I had at the time, which was to write a book about certain practices that I knew, through my own direct experiences, were uncommon yet uncommonly productive. And so, I thought this is the book that I’m going to write. And where the synchronicities came in is that when I was finished with writing the book, it became a very different book than I imagined. Part two was what I ended up writing, but part one, I never in a million years dreamed of it. But in the process of really doing research to validate my thesis, I realized, oh, man, I was put on the earth to do this work. This is what I’m supposed to be doing. I’m not supposed to go back to financial services. So, it wasn’t like I thought I’m going to have a bigger audience this way. It was just like I jumped in the river and the river took me there.

Let’s start with your book, “Lead from the Heart.” You talked earlier about how the fact you went into challenge these ideas about weakness or softness in leadership, a book called “Lead from the Heart,” some people might immediately see that on the shelf and be like, “No, it’s not for me. I’m not into that stuff.” What is it about leadership that we think needs to be a little bit hard and cruel about these things?

I think we think that people don’t want to work is one, and that we need to oppress them. And that oppression often comes in less the micromanagement side, although people have that instinct, but it’s really around fear. It’s really around creating a sense that if you don’t perform, something really bad is going to happen to you. And that works on people, but it happens to be very, very destructive to their spirits. And so, you can’t sustain it for very long. And yet, many managers who use fear are going to keep going to the same button over and over and over. Because, unfortunately, fear is a very powerful motivator. To directly to your question around this idea of softness, I was told, I paid a lot of money to a consultant who told me, you will fail if you go out with this title. So, call it “Killer Engagement” or anything or than because you don’t want people just going, well, that’s, I’m just going to say it, that’s bullshit, or somebody seeing that says, “Well, that guy’s either a spiritualist, a religious nut, or he doesn’t get business, but either way, it’s not for me.” But at the end of the day, the synchronicities that led me to call it that was that, A, I realized in my exploration of what was I doing to people that drove extraordinary performance so consistently, regardless of the people, whether it was a man or a woman, young or old, educated, not educated, whatever the job was, I consistently got great performance out of people that I realized that I was affecting the hearts in people. And I was smart enough coming from banking and financial services to know, oh, my God, I’m dead on arrival if I go out there with this, telling people that I’ve been affecting their hearts. But I ended up getting corroboration around this from science and went and met with a world class cardio surgeon, cardiologist, and just basically said, Look, between you and me, I think I’ve been affecting hearts in people. And is there any science that would support that?

Like actual hearts you’re saying?

Like actual hearts, literally, yeah. So, this is not a metaphorical thing, although people use it metaphorically. But at the end of the day, what I really confirmed is that much as we like to think we’re rational beings, I think therefore I am, we are driven by feelings and emotions. Feelings and emotions drive our behavior. They drive what we care about, where we commit ourselves. And so, when I realized that that’s the truth, then I said, Well, okay, is it just in the brain? Or is it dispersed? Because it would be kind of cool, honestly, if it was in the heart. And what she told me is that for a very long time, we had no scientific evidence that the heart did anything more than pump the blood. And so, science basically said, everything’s in the brain. Well, now we know that the heart and the mind are connected, we have clear confirmation that human beings are hardwired to thrive on positive emotions. And we also know that no emotion lasts very long. So, as it was confirmed to me by an organization called the Institute of HeartMath, which has been studying intelligence of the heart for the last 30 years, the head of research and also one of the cofounders, he goes, your brilliance as a leader, whether you knew it or not, was that by supporting people, caring about people, coaching people, making people feel safe, valuing them, outwardly telling them how much they meant to you, and how much you appreciated having them on their team and teaching them everything you could, all these things, he said that was drip, drip, drip, drip of positive emotions. And when people have that steady diet of positive emotions, you put them into their optimal level of performance. So, no surprise that you got extraordinary performance out of people because you were basically putting them into a situation where they could almost do nothing but excellent work because all their needs were being met.

Walk us through a few of these things. You alluded to a few things. But what are these counterintuitive things that you did as a leader that lead to success in your teams that other people might think that’s too weak. I don’t want to even try that. It’s not going to get results.

Caring about your people individually, for one, just genuinely care about them. I mean, we have this transactional view of leadership, which is to say, you come into work, Neil, you have a paycheck, if you do good work, you get a bonus at the end of the year or some sort of financial rewards. That’s the fair exchange. I agree to it. You agree to it. So, I don’t really need to do any more for you. That’s the bargain. And so, many managers think I don’t need to get to know people. I don’t need to manage them any differently. Everybody’s going to have to adapt to my style. And what I’ve discovered is that what people want is to know that they’re valued for who they are, for their uniqueness, for their unique talents, for their unique personality. And they want to be made to feel safe, which Maslow put at the very bottom of his pyramid for a reason. So, if you’re managing with fear, you’re doing just the opposite, you’re making people feel very much unsafe. So, what I tried to do was to get to know people personally, not so that I can have them over for Sunday dinner or go out for a beer with them. But so that I knew what their motivations were, I knew what they were trying to accomplish at work, what I could do to help them, how they wanted to be appreciated, any accommodations I could make, if they had a long commute, or if they wanted to coach their kids’ teams, anything that I could do to support who they were as a person ended up being, through reciprocity, rewarded to me. People were so grateful that I knew who they were, that I cared about what was going on their lives, that I knew what they were trying to learn, that I gave them opportunities to grow, align to those things. And when you do those kinds of things for people, they’re just so grateful. They’re like I want to do more for this guy because of what he’s doing for me. So, you end up getting far more from people than you even give to them. But it requires that it be authentic. You can’t fake this. You have to really love people. And you have to want to see people thrive. You can’t compete with your people. You can’t be threatened by your people. So, it takes a certain mindset. But if you can operate this way and manage people this way, the rewards are just extraordinary.

I like what you said about authenticity because you said the first step is just caring about people. But that’s not something that you can just say, yeah, tomorrow, it’s on my checklist, care about people. If you find yourself in a position where you think I have this team, I kind of care for people. But in the end, I think I’m a little more transactional, what are some of those first steps you can take to build more of a fondness and care for those around you?

I think you have to ask yourself the question, first and foremost, which is do you think you can get there? In your heart of hearts, are you somebody who really thrives in the success of other people? Or is it more about you? And really, we kind of know that mathematically, 3 out of every 10 people on the planet have this inclination to really when they see other people do well, they feel like a sense of satisfaction themselves. They’re genuinely happy for other people. Not everybody’s like that. And so, if you really don’t like that, if you really don’t like giving to other people, and coaching people, and encouraging people, and really being a support for people, then maybe an individual contributor role at a high level would be a better role for you. So, I know it sounds sort of like that’s not the question I asked. But I think it’s important for people to say don’t try to teach me something that I really don’t want to learn, or I know inside of me that I probably am not going to be good at. But I think if you’re instead saying, no, I really want to do this. How do I do it? I think it’s really just making time on a consistent basis to have a regular conversation with people.

One of the things that I’ve discovered, and we were talking earlier, Neil, that I have my own podcast, and I’ve had some truly extraordinary people on, and research has shown that what people don’t really want from us as managers is the constant, “Hey, Neil, if you could just work on this a little bit more, I think you could get better at this. Or you know that financial analysis you did? There were some pieces there that, it was good, the numbers were there. But I didn’t really like the presentation. And I don’t think you’re really thorough enough.” And constantly just giving people feedback. What they want is our attention. “How are you, Neil? What’s going on, Neil? Is there anything that I can help you with?” And that seems counterintuitive because it’s like, well, then what am I doing here? Just having a conversation with people? It turns out to be very powerful. It turns out that what we really don’t want all the time is to be criticized or graded, evaluated. What we want is somebody just to be on our side, just to be there for us. So, it’s just like, “Hey, Neil, I’m just checking in with you. How are you? How was your week? What’s going on? Tell me if there’s anything going on that I need to be aware of. Anything I can do to help you?” And those conversations sort of unfold, and you end up getting to the business aspect. It’s just you don’t have to come at people with an agenda all the time. So, why is that important? Because it makes people feel safe. It makes people feel like I got a normal relationship with this guy. I don’t always have to be on. I don’t always have to be prepared. And not everything has to be buttoned down all the time. It takes stress off of people.

Tell me about a time when you were working with somebody or you have a story about when an employee went through a really serious personal crisis. Let’s say that there’s something going on in their work that was really distracting for them or required them to be away from work for a long time. I feel like especially as young leaders, we’re not really sure how to respond to that. Should we engage more? Or should we pull back and give people space? What kind of boundaries should we create in those situations?

Oh, wow. It’s an interesting question. I’m going to tell you, before I tell you the situation, I want you to know that my boss at the time told me that I didn’t handle it well. And the reason he told me that was that I gave the person too much time. So, here’s the scenario, and I’ll explain what I learned from it, and then give the lesson for the audience. So, basically, what happened was, so you know the bank branches where people go checking accounts and mortgages, they’re all over the place. I had a bunch of those. I was running a big market of those bank branches. And at the time, all these branches were open on a Saturday. And one Saturday, this manager was working, and her husband called her and said, “You’ve got to get home. Our son has got a health issue, like a serious health issue.” And she didn’t even bat an eye. She grabbed her purse, walked out the door, didn’t tell anybody just, floored it, got home, and her five year old son was was dead. And so, she went into a deep, deep, deep depression, blamed herself, “Had I been home, this never would have happened.” And it turned out that there was a congenital problem. There was just a ticking time bomb for this poor little baby. And but she ended up taking a leave of absence. And she was a really talented person and somebody that I had held in very high regard. And I was just very empathetic. So, I gave her plenty of time to go on a leave and have the funeral and sort of come to terms with this. And meanwhile, the people that were running the branch were really strapped because they didn’t have her around. And it was a very big, very busy branch. So, they were like one man down, but a very important man down for that period of time. So, she ended up coming back. And then I started hearing from her employees, particularly her assistance, that she wasn’t dealing well, and that she ended up leaving in the middle of the day, or would walk out the door for four or five hours and then come back and was very erratic. And I just was feeling very empathetic for her, ultimately had to terminate her employment, which was very difficult and very painful. My boss said, “You let that go on too long.”

And so, the lesson that I learned was I don’t regret the compassion. I demonstrated to everyone who worked for me, Neil, that if that were them, that they would have a boss who really cared about them in their most difficult time. So, I never had my peers say to me, or my employees say to me, “You let that go on,” never once. But at the same time, you always have to keep in mind that it’s a business, and that you have to let the business run. So, what I could have done was just say, “Hey, I’m going to replace you, and when you come back, we’re going to put you somewhere else.” Or I could have said, “Unfortunately, this is enough time that the business can afford. And so, come back when you’re ready, we can talk about another position. But for now, we’re going to…” I had a lot of options that I didn’t really pursue because I think I was rooting for her. I think the mistake that managers make is we think, “Oh, that’s such a sensitive issue that I’m going to stay out of it.” And what they really want you to know is not that you intend to solve their problems, but that you know about it, and that you care about them. So if you just say, “Just know, Neil, that I know that this has to be an extraordinarily painful situation and time for you. And I’m thinking about you and I want to give you as much support as I can because I care about you.” I didn’t say I want to solve your problem. I just said I want to help you. I want to be there for you. That’s what people really want to hear.

Because when you’re in that time of crisis, the last thing you want to feel is like, “Oh, I have to get back to work right away because if I’m not there, if I miss a day, then no one cares about me there. So, I’m dead anyway.” So, I like your perspective on that. Let’s move on to talk a little bit about generations. In your speaking and the times you’ve had to interact with people, what have you felt has there been any change in how you meet the needs of people who are continue to join the workforce, who are younger? Do you feel like it’s the same thing, “I just care about people,” or are there some nuances that people need to interact with as they engage with younger people?

Well, this month right now, actually, is the graduation of the very first Gen Z. And so, we’ve got, really if you think about it, we’ve got like at least four, maybe in some companies, five different generations of people that are working together. And so, I think that the thing that I really want to punctuate more than anything is that regardless of how old you are, the need and desire for everything that I’m talking about, to have a boss who knows you, cares about you, values you, appreciates you, grows you, creates a safe environment for you, that’s a human need, doesn’t matter what industry, doesn’t matter what country. At the same time, baby boomers, and maybe even Gen X, they allow or tolerated, they had a belief system, if you will, collected belief system, which is I need a job, I need a paycheck. And that whenever crap comes with it, I’m going to accept. Millennials didn’t and millenials came in and said, “I’m not going to accept crap when it comes to work. And more importantly, I’m going to expect much more than my parents did. I want a boss who cares about me. I want a boss who coaches me. I want an opportunity to learn. I want to be told I’m doing good work and hear frequent appreciation.” And so, they’ve been sort of pushing leaders to do this.

And so, what happened is when millennials really started coming in, they got this bad rap from baby boomers primarily. But this idea that they’re needy and they’re disloyal. And I look at them in a very different way. I look at them and I think, well, what they did was they observed their parents, they observed how their parents were treated, how the bosses were very demanding, and the bosses weren’t necessarily very supportive of them. And during the recession, of course, when things went south, a lot of people were killing themselves at work. And then they lost their jobs because the company’s first instinct was to lay people off. And so, millenials were watching all this and saying, hey, I want no part of this. If this is going to work for me, it’s got to be a win-win. So, I give them a lot of credit for changing and really forcing the kind of leadership that I’m talking about because they are willing to leave, they are willing to quit. And initially it was, well, they’re just flaky and they’re not loyal. And now I think companies have come to realize that they will be loyal, they want to be loyal, but you got to give them a reason to do it. So, I’m really grateful to the millennial generation. And I’m sure the Gen Z is going to continue with this. They just want a different style of leadership. And they’re going to keep looking until they find it. And what I’m doing is trying to tell the leaders and really organizations, CEOs, that if you don’t start hiring managers who have an inclination to manage this way, you’re not going to succeed, because this is where people are.

I think that’s fantastic. And like you said, if 3 out of 10 people have the innate ability to do this, you have to be really selective about those things, or else really try to build into and educate those who don’t have it but want to build those skills.

A lot of times what happens is, yes, right, completely 100%. And I think one of the problems in the existing paradigm in business in how we tend to pick people for leadership roles is we say, well, they were the best architect. So, we should put them in charge of all the architects. Or they’re the best attorney and we should put them in charge of all the attorneys. Or they’re the number one salesperson, dot, dot dot, right? And the inclination to be the best of any of those isn’t necessarily the same inclination that one needs to have in order to be the best manager. So, one of the examples that I use when I speak is a guy named Bruce Bochy. And Bruce Bochy was the backup catcher for the San Diego Padres. And just to be clear, the San Diego Padres have been a mediocre baseball team for 50 years. I live in San Diego so I know this painfully. But he was the backup catcher, which should tell you something, right? So, he wasn’t even good enough to be the starter. But what he was was somebody good enough to make it into the majors. And he played for nine seasons, which is pretty impressive, right? Not great stats, but he was somebody that they thought was good around players, and was a good catcher. And so the Padres came to him and said, “Hey, we’d like to make you a coach,” and inevitably they made him the manager. And in 1998, he took the Padres to only their second World Series. And they got clobbered by probably the greatest New York Yankee team ever. They lost four straight. And the Padres, who’d only been to one World Series since 1969 said, “Oh, we’re going to let you go.” So, he went off to San Francisco. And in his first seven years, you probably know the rest of the story, he coached the San Francisco Giants to three World Series in seven years, wins. He won the World Series three times. And he will go down in history as one of the greatest sports coaches of all time. And you look at that, and you go, well, how come? Well, because he’s capable. He was a capable player, he wasn’t necessarily the best. But what he was really good at was assembling teams, seeing talent, bringing it out, building cohesiveness, all of that. And he didn’t compete with them. He wasn’t a competitor. It didn’t hurt him to see somebody do a better job of catching or a better job of hitting. That was the mindset he had. Like, that’s my job, I want you to do well. And so, he’s a perfect example of an organization that said we don’t necessarily have to have the big home run hitter, or the guy that led the league in hitting to be our manager because that drive to be number one almost puts you into a mindset of I’m competing with other people. And we don’t want to compete with our boss.

Mark, this is great stuff. I love what you’re saying. I’m excited to dive deeper into it. Why don’t you share with people a little bit more about where people can find you, your podcasts, and everything else?

So, the name of the book is “Lead from the Heart: Transformational Leadership for the 21st Century,” and you can find it on Amazon. It’s now being taught in seven American universities. And I think one small college in Ireland. And the best way to get me for anything, including the podcast, markccrowley.com.

Well, thanks so much, Mark. It’s been great. I appreciate your insights and we look forward to learning more from you.

Thank you, Neil. Honored to be here.

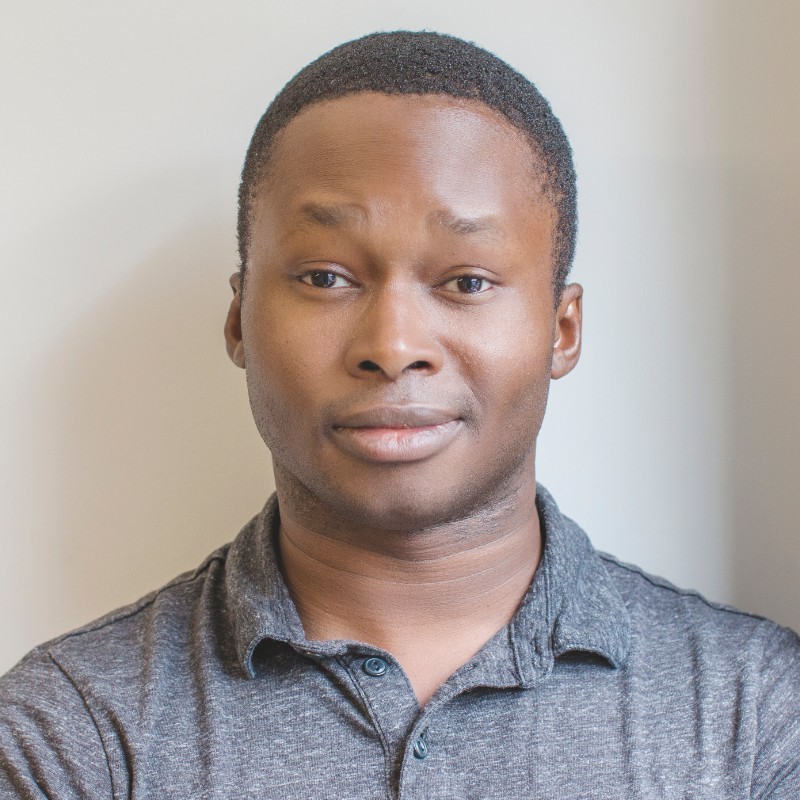

Drawing on decades of experience as a senior leader for regional and national financial institutions, Mark C. Crowley delivers an impactful message that leaders who intentionally engage the hearts of their employees will be rewarded with uncommon (and highly sustainable) performance and achievement.

Mark outlined a blueprint for successful employee engagement in his bestselling book, Lead from the Heart: Transformational Leadership for the 21st Century which consistently ranks as an Amazon Top-100 bestseller in workplace culture and is being taught in nine Universities across America, including the Leadership Development Ph.D Program at Brandman University.

Mark was named a “Trust Across America 2016, 2017 and 2018 Thought Leader” by TRUST! Magazine, and was additionally spotlighted in Forbes Magazine which asserts that his innovative thesis represents “the future of workplace leadership.”