What are we talking about?

Understanding humans, specifically building the right environment for humans to work and live better.

Why is creating a good environment for humans to work and live better important to the future of work?

A workplace that is focused on being a positive place for humans is going to be extremely important in the future. If you create a culture that honors interpersonal relationships and practices great communication, people will enjoy working for your company and you’ll help them live better too.

What Max Yoder taught us about how to look at creating a great work environment

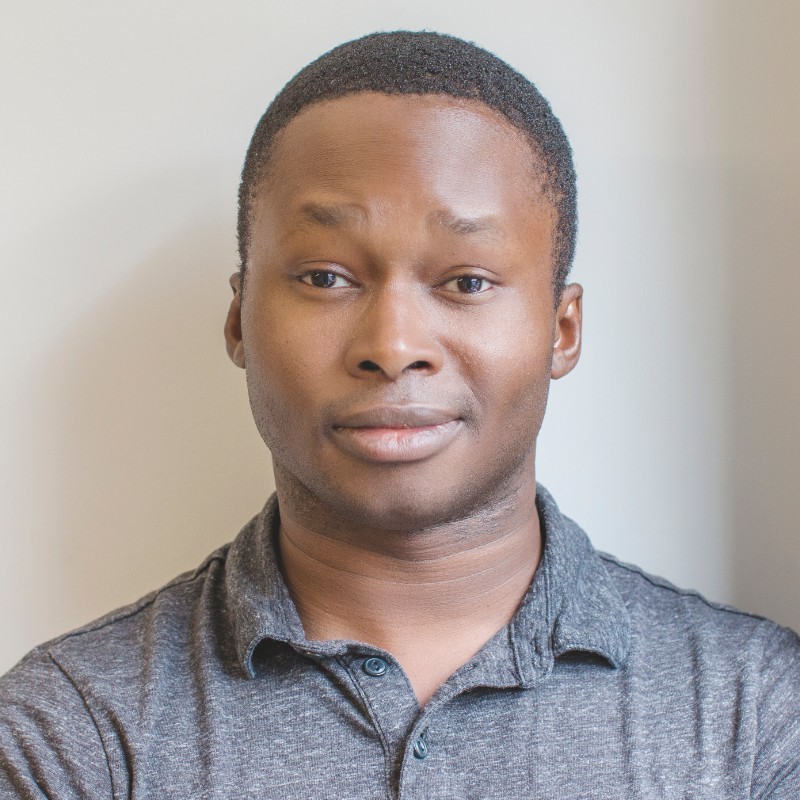

Max Yoder, author of Do Better Work, and CEO of Lessonly thinks a lot about how to create a great place for humans to work well. The book highlights 8 key practices that leaders can implement to help achieve Lessonly’s goal to “help people do better work so they can live better lives.”

Max is a student of self-reflection and understanding what makes people tick. He’s also a huge fan of Carl Jung and others who have helped people reflect on the human experience. Max said, “My job is to understand my darkness so I don’t pass it on to someone else. Self-improvement is going to be my job until I die.”

The two big themes of the book are clarity and camaraderie. If you have both of these in your company, you will have a successful culture. The more you can be clear about what a job entails, the more likely someone is to be successful at it, and have good days. However, “Clarity at work is not something that persists. It must be built and rebuilt.”

Camaraderie means that you actually enjoy working with the people at your company. Max says that if you like each other and know where we are going, we are much more likely to make significant progress.

Leadership is an important part of building the right culture. However, many of us have inherited a distorted view of leadership that means a leader should always know what to do next. Max says, “Leadership is not knowing what to do, but committing to learning what to do.” If your team (and you) assumes that you know everything, they will assume you already see the threats and opportunities. This is a complex and chaotic world; how could you possibly know what to do in every situation?

Max sees a big connection between work and home life as well. A good day at work often transcends into a good day at home, and if we are helping people lead better lives, then it’s all worth it.

Be sure to read Max’s book. It’s a quick read and you’ll definitely walk away with something to think about and at least a few ideas on how you can create a better culture.

Learn more about Max Yoder

Max’s first episode: Work Minus Intuition

Today we’ve got a repeat guest on the show. We have Max Yoder. He’s the CEO at Lessonly and he’s also the author of the book “Do Better Work“. How have things been, Max? How are you?

Doing great. Thanks for having me on again, Neil.

It’s always a pleasure to have you on. You are a guy who seems like he’s always on the path to improvement. Someone who always is looking for ways to better yourself. This new book you have is very instructional. But it almost feels like we’re reading your journal as we’re going through it and seeing into your soul a little bit. Have you always been that kind of person that’s always looking for ways to improve and get better?

I don’t know. I think more than ever I’m clear on the work that is required of me. And that work is how do I get myself in a spot where I minimize my anger and I minimize my sadness. It’s not to not be sad or angry, it’s to understand my anger and my sadness, and embrace them so that I am just a less volatile individual. I think we all can be volatile individuals. And if we’re less volatile in life, we don’t pass kind of our darkness on to somebody else. So, my job is to understand my darkness so I don’t pass it on to somebody else. So, self improvement is going to be my job until I die. And I feel like it’s the one thing I can control is how do I grow myself so that I am not throwing my shadow on everybody else.

That’s so important. I feel like as we move to the future, for leaders to have that heightened sense of self awareness of really understanding who we are as people, what drives us, what we like about it, what we don’t like about it, find ways to root that out, because not only are you learning about yourself, you’re learning about the people in the process, too, right?

You bet. I mean, Carl Jung has been hugely instructive for me over the past year. So, if anybody out there listening has any ideas of how do I bring myself into a more holy place? When I say holy, I mean whole, like a whole person instead of a partial person. And Carl Jung would argue it’s this thing called individuation. And if we all do it, or even a fraction of us do it, his argument is we create much safer, kinder, warmer places where people can actually develop and not be so dang scared, and I liked the sound of that.

Yeah, sounds awesome. So, last time, we had you on the show, we talked about Work Minus Intuition where it was this idea that instead of just guessing how people are feeling, guessing how we should go into things, we should actually ask. We have the ability to communicate, we can do that. We talked about nonviolent communication, which is one of your favorite topics. So, I really learned a lot from that. Now you’ve come out with a new book, “Do Better Work“. So, tell us how that came about.

The big idea was our mission statement is help people do better work so they can live better lives, and defining what better work meant was important to us as an organization. Kyle Lacy, as our chief marketing officer, he suggested… I’d been writing weekly notes, I still write weekly notes. I appreciate you being a reader of them. I always appreciate your comments on them and your thoughts. Kyle said, “Hey, let’s define how we think about work.” And that was a pretty big ask. I was nervous as heck to do that, but it was the right push because if we’re going to help people do better work, we should be clear about what we mean by that. Not this idea that we own the idea of better work. We certainly don’t. We want it to be a movement that people embrace and make their own. But what do we mean when we say it? So, the book went through a bunch of different transitions while I got out of my own way. And when I say get out of my own way, I mean, first, I started writing a book as though I thought I should write a book, like, I “should”ed myself into writing the book. “I should do it like this, and I should do it like that.” And ultimately, I took a long time to get out of my own way and just be, like, what is genuine to my soul and my spirit? And as soon as I got to that, which, like I said, took a while, everything started to go much more smoothly and the themes started to reveal themselves. Because you have themes, and you and I have themes in me, and we’ll find them through self exploration. And that’s what book writing helped me do is yourself explore and find those themes to find what better work meant to me and to us as an institution. And that’s been really rewarding.

And like I said, the book is instructional. It is tactical. But it also reads almost autobiographical. It reads like the story of the company, too. So, I think that comes out strong. I want to get into your mission statement. You said, “Do better work, lead better lives.” So, especially the second part of that, lead better lives, what do you feel like is the connection and you’ve seen with your own employees and team members, between getting better at work and getting better at life?

So, where we think we play a role with our training software, we make training software that helps people learn and practice. What we’ve found is that when you’re clear with your teammates about what good work looks like or what a successful job looks like, when you’re clear and you spell out the behaviors and you model those behaviors, people are much more likely to engage in those behaviors. But when you leave it ambiguous and you make people guess, they’re much more likely to guess something different than you hope they would. So, training software is just about spelling it out so people don’t have to guess anymore. And what we see is that the more we can spell out what the job looks like and the success in the job looks like, the more people do it, and we know that a good day at work transcends to a good day at home, or often it does. If you walk out of your office, Neil, and you see somebody in the street after a good day, you’re a different person to that individual, just like I am. And our way of impacting that better lives part is just if we can help you do better work, we know that’s going to have a material impact on your life. And we know that it stinks to not feel good at your job, to not feel equipped in your job, and we know you carry that home with you, too. So, you’re going to walk home and you’re going to greet people and you’re going to meet people in the street, but you’re also going to walk into your house. And whether it’s your kids or your spouse or any other loved ones, if you had a better day that day at work and you felt more competent and confident in your job, that goes a long way to you being more joyful at home.

This is awesome stuff, Max. I love the holistic viewpoint you’ve seen, I’m assuming your practice, even in your company, the idea that what happens at work, it’s not just like we close it off. And the same thing what happens at home, we bring to work, but what happens at work we bring home, too. And so, the better we can do at creating good systems, good communication practices at the office, the better our whole lives will be.

Yeah. It’s something that companies, I think, just want people to interpret, like we talked about last time being intuitive. I think often it’s just left in the ether of, well, just look around. Just do it like we’re all doing it. And not everybody’s doing it the same way. And it’s not always clear why whatever you’re doing works and which parts you want me to copy and which parts you don’t. So, let’s just be clear as we can. And clarity is not something that persists. Clarity is something you have to continually build and rebuild, and in a given day, some catastrophic life event, inside or outside of the business can really change how much clarity we have about what we’re doing and why we’re doing it. So, our job is to create clarity as a two way street where you and I, if we’re teammates, or if we’re in any relationship, we work together to find clarity. We don’t just expect it to come to us. So, the employees need to be asking for clarity. And if they’re not getting the clarity that they need, first and foremost, are they looking inward and saying, “Am I doing my part to find it? And being persistent in the finding of it?” And the companies need to do their part in creating safe spaces so people can communicate and ask questions, and they’re doing their best job to proactively communicate. Nobody’s going to nail this, right? But we can do it 1% better every day.

Yeah, I like that. So, clarity is one of the two main concepts in your book. You have clarity and then camaraderie. So, I want to hear, obviously, you’ve had a lot of experiences in leading this company and others. Why are those the two that you settled in on?

So, let’s start with camaraderie since I just talked a bit about clarity. Camaraderie is all about a mutual trust and respect between people. And it really boils down to do we like one another well enough to show trust and respect to one another, which I think is kind of a low bar. I think everybody deserves trust and respect as a starter. But everybody’s wired differently, right? That’s just me. If we like one another, and then we’re clear on what we need to do, and that’s the clarity part, where we’re going, why we’re going there, what your role is in that pursuit and what my role is in that pursuit, we’re going to make a lot of progress. So, the big idea is I think we need to both have trust and respect. We don’t need to be the best of friends, right? We don’t need to have everything in common. But we need to recognize that one another has value, worth, dignity, and good ideas, just like every one of us also has not so good ideas. But if we have that agreement of like, hey, we’re both people we enjoy being around in some way, shape, or form and we know where we’re going, we’re going to get a lot done. If we only have one of those things, though, and not the other, I think things get lopsided. If we have clarity in a company, but we don’t have camaraderie, we start to actually undermine future clarity, because we stop communicating nearly as much as we otherwise would if we had the camaraderie component. And if we just have camaraderie, but we don’t know where we’re going, we’re really just hanging out at that point. We don’t really know what to work on and why it’s important. So, for us, it just boiled down to, as I wrote the book, we started to read the chapters and realized those are the two themes that came out through the different behaviors that I talk about in the book. And I’m sure there’s more. But those are the parts that I felt most comfortable talking about. And I think they get you a really long way in making progress at work.

I want to talk about one of my favorite quotes from the book which said, “Leadership is not knowing what to do but committing to learning what to do.” I feel like that’s a really powerful quote, especially for this day and age when we talk about future, the future of leadership, future of work, there’s going to be more and more that we don’t know as we progress into the future. Things that are known are just going to kind of get codified and they’re easy to find, but admitting that you don’t know things. So, tell us more. Unpack this quote a little bit more for us.

Sure. I mean, everything’s context dependent. What works in one realm doesn’t necessarily work in another realm. So, I’d argue, the bigger the world gets, the less we know, and we’re just continually going to be searching for the right way for us, not the right way for everybody, but the right way for our relationship or our organization or our team. I think there’s just this big myth that people, and myself included, that I brought into a leadership role, which was believing that I needed to know the answer if I was going to be somebody worth leading other folks. So, this idea that leaders know the answer was in my head when I started leading, and I think it’s a fiction that got there because we just don’t have enough vulnerability in leadership, where people speak openly about the fact that they have learned along the way. The closest we get is fake it until you make it. I think really what that means is learn along the way. If leaders are supposed to know the answer, well then, I can’t ask a heck of a lot of questions if I’m in a leadership position because I’m showing that I’m not a leader at that point, right? Because I’m supposed to already know what to do, not find what to do.

But if I get to say, leaders learn the answer, which is absolutely true, I can ask as many questions as I want, I can seek the advice of anybody in the company. And I empower everybody else in the company to behave the same way. But if we have to posture and act like we know the answer, and we kind of dominate life, and we know all the directions that work, we’re not going to get very far. We’re going to shut things down, we’re going to shut communication down. And I think you shut it down in two really important ways. If people believe that you know the answer, and you behave like you know the answer, they’re going to be less likely to point out opportunities that they see, because they’re going to assume that you already see them or that you’ve already decided they’re not great opportunities. They’re also going to be less interested in pointing out the threats that they see because they’re going to think, “Well, Neil probably knows that that’s there because Neil seems to have it all figured out.” So, we limit our ability to see potential roadblocks ahead and also potential opportunities ahead because people just assume that you got it covered, or I got it covered if I behave that way. What signal am I sending to say, “Just ask me. I know what to do”? It certainly isn’t true. And it’s limiting my ability to communicate.

And I think if we think about a great relationship, Neil, communication is the root of a great relationship. The stronger we communicate, the clearer we communicate, the more we work on our communication with one another, the stronger our relationship is. The more our communication breaks down, the weaker our relationship becomes. I think really a one to one connection is how well are we communicating. Of course, we have to embrace whatever we’re learning in that communication and adapt and put it to work. But I think communication goes a big way in building a great relationship. If we posture like we know the answer, that’s a challenge. So, I think when you get in a leadership position, you got to say out loud, “Look, some of these stuff, I feel more confident, and some of it, I don’t. And I believe we can figure it out, but I’m not precisely sure how.” And that is, to me, what vulnerability is, saying, “I’m confident we can figure it out. I just don’t yet know how and I’d love your help.” That to me is what vulnerability is.

Yeah. And that sounds like leadership to me. That’s what it should be. We hear that fake it until you make it a lot, which is almost being honest with yourself that you don’t know. But you’re not being honest with the people around you.

You’re posturing. You’re faking it. I think everybody else around you immediately breathe a sigh of relief if they don’t have their sword and their shield up too much. And I think everybody can carry around a sword and a shield where we’re defensive or offensive in a defensive way. If we can drop those things when we see somebody who is being vulnerable, it’s really empowering and it’s contagious. And if somebody else is allowed to say they don’t know then I’m allowed to say it, too. And I think we need more people going, “I don’t know,” because this is a complex and chaotic world. How could you possibly know? We’ve got to communicate every day.

So, I think that leads into another point of the book that I really enjoyed, which was where you talked about the importance of starting with yourself, not expecting everyone else to change. There’s probably a feeling that you’re going to read Max’s book, you’re going to get through it, like, “Man, I know five people who need to read this and start applying it and I’m going to hand it out to my staff.” I know, obviously, for book sales it would be great if people just did everything like that. But what’s the impact, the difference between just making everyone think about these concepts and expecting them to change and just having one person who’s in a leadership role actually do this stuff?

Yeah, I’d take the one person all day long. Book sales be damned. And I don’t think I’ve thanked you yet on this podcast for taking the time to take the book in like you have and really consider it. So thank you. Yeah, I’d take one person any day who applies and practices the behaviors than 30 people who read the book and never diligently practiced any of the concepts. Any one of these concepts falls flat on its face if somebody doesn’t embrace it and say, “1% of the time, with self compassion, I’m going to apply these behaviors.” I say 1% at a time because you’re naturally probably doing a different behavior. So, 1% of the time how do you integrate a new behavior into your work? If you’re not getting agreements right now, there’s a chapter in the book, how do you get more agreements? 1% at a time. Getting people to agree on the behaviors they want to see, 1% at a time. And how do you forgive yourself along the way, which is a self compassion part, when you drop the ball, as you will? There’s this thing called lapsing in the process of building a new behavior or building a new strength. We lapse back to the old behavior. And I think often in that moment, there’s a tremendous amount of judgment. I think that judgment comes from a really fundamental misunderstanding of what it means to know something, and what it means to do something.

So, you can know a lot. I can put the whole wealth of the world’s information into your brain. And it doesn’t mean your behavior changes because knowing something intellectually is very different than knowing something in your heart and soul. If you know something in your heart and soul, it’s either because you’re already naturally doing that thing, or you’ve practiced it enough that it becomes second nature. That’s what knowing in your heart and soul is. I think we know things in our brain, and we don’t practice them and we wonder why they don’t take in our behavior. It’s because we didn’t practice them. So, the intellectual understanding of any of these concepts isn’t going to move any needles. The demonstration with self compassion of any of these concepts will move the needle. And you control you, not anybody else. So, it’s easy to look outward and go, “Wow, X, Y, and Z teammates, they don’t do any of this. How foolish.” It’s much harder to look inward and go, “What parts of this do I not do consistently? Am I possibly projecting on my teammates my frustration with myself?” And then start there, because that’s a very human and real thing to do. I do it. And I don’t blame anybody else for doing it. But let’s start making that change of just looking inward and going, “I control me and how well am I doing there?” It’s way easier to look outward.

So, we’ve been talking about that people need to practice the concepts. We haven’t really talked too much about the specifics in the book. So, we’ll just highlight a few of them because there’s a lot for people to go through. But I want to talk about looking for opportunity. When people realize that at any time in life, in business, you run into lots of challenges. You didn’t hit a mark, you run into something that you feel like is unfair, or some situation that you want to get out of quickly. But changing your mindset in that is important. So, lead us through that discussion.

So, looking for opportunities is this idea that challenges are inevitable. Like I said, the world is chaotic. The world doesn’t care what your plans were because it just is chaotic. So, you’re going to have a plan that gets you to a goal, and in the pursuit of that plan, something’s going to go wrong, and the plan might entirely implode. And in those moments is natural to tell yourself a threat story, which is this is bad. That’s what a threat story is. “This is bad. My situation is worse now that my plan failed.” So, if you’ve ever been dumped, you probably told yourself a threat story. “This is bad. I just got dumped.” I know I’ve been dumped. I’ve told myself threat stories after being dumped. Telling yourself an opportunity story is saying, “The plan isn’t going the way that I hoped it would. But this might be an opportunity for me to actually learn more than I otherwise would have. It might be an opportunity for me to reflect on the goal and find out if I actually still want to go after that goal in the first place,” right? Sometimes our plans fail, and they allow us to look up and go, “Do I still care about that goal that I was after or was I just chasing this plan out of an escalation of commitment?” They basically, because the world’s chaotic, it throws curveballs at you that are negative in the moment, but later can be very positive if you allow them to be.

So, in the moments where something fails, one of the things that I recommend in the book is this approach by Scott Dorsey, which is list the alternative plans. If you still want to go after whatever the goal was that your initial plan failed. You had a plan, you had a goal, you still want to go after that goal, start writing your alternative plans. And this is what Scott does a ton. He does it every time something goes wrong at Lessonly and I ask him for help. We start listing out the alternatives. And then we pick the top three, then we pick our top one. It’s a very simple exercise to get you back on the horse. Now you have a new plan again, and you can start building momentum again. It’s not to say that you shouldn’t go, “Oh, that stinks that the plan didn’t go well.” I think you should identify when something doesn’t go like you want it to and investigate that feeling. I don’t think you should shut it out and act like you’re an internal optimist if that’s not how you feel. I think you should investigate those negative thoughts. But looking back on your life, I want to ask anybody who’s listening, think about a time when something didn’t go the way you wanted it to. And now you look back on that thing, not going the way you wanted to, and you’re grateful. That happens all the time. And it could happen tomorrow. And in that moment when that thing tomorrow doesn’t go how you want it to, remember all the times that you’ve been grateful that you have not gotten what you “wanted or needed”, and you look back and say, “Phew, I’m so happy.” Happens with me with my wife right now. She’s the woman I love. And I had to get dumped before her to find her. My first business was Quipol. Didn’t work out. It had to fail for Lessonly to exist. I didn’t get the jobs I wanted after college, and then I met Kristian Andersen. He became my perennial business partner. I look back all the time. And now when something happens to me, I’m just, like, I don’t really know what I need. So, let’s take this in stride. I’m disappointed the first plan didn’t work out, but maybe it’s great for me.

So, last time, we talked about nonviolent communication. This time in the book, you introduced a few other new concepts, specifically one called appreciative inquiry. So, walk us through what that means.

This is a game changer, man. This one has changed my life, maybe more than any of the others. I’d say nonviolent communication, appreciative inquiry, I could probably go on. But appreciative inquiry is this idea of, I’m just naturally wired, Neil, to look for what isn’t working and focus on that. I’ve lived most of my life with the belief that the only way to improve the world is to find problems and solve them. I think we have a cultural bias toward problem solving. Where are the problems? Let’s fix them. To the point that if you asked, next time you get a group of your teammates together, and you said, “Let’s just spend the whole meeting talking about things that are going well,” if your experience is anything like mine, you’d get a lot of eye rolls. “Well, why would we do that? There’s no point. There’s so many problems to focus on. Why would we talk about things that are going well?” Well, the big idea of appreciative inquiry is if we know what’s working, we can do more of it. And in the pursuit of doing more of what’s working, we will naturally make the world better because the more time we spend doing the things that work, the less time we have to spend doing the things that don’t. So, naturally, we begin to improve our environments. But the problem with appreciative inquiry is there’s an assumption. I don’t mean the problem with the theory. I mean, the reason I think people aren’t drawn to it, or the reason it might seem silly is people think that things that are working are problems already solved, or boxes already checked, missions already accomplished, so why bother?

And the reason you bother is not everybody on the team necessarily knows what works and what doesn’t. So, the more you share things that are working in the company, the more people can take notes and go, “Oh, I’ll try that, too.” So, naturally, we start to spread good information. And you can start doing this today by just looking around your team and going, “What’s going well and how do we do more of it?” Or looking around your relationship with your husband, wife, significant other, whoever it is, saying, “What’s going well and how do we do more of it?” Find the places where you’re in the pocket where you’re singing together, where things are working, and make sure that you highlight your appreciation for those things, because people might go, “I hadn’t noticed that I really value that as well until Neil said it or until Max said it. I didn’t notice.” And then they might adopt some of those behaviors, too. So, there’s this bias toward problem solving. Appreciative inquiry is kind of saying, “Let’s look for what’s working just as much as we look for what doesn’t work.” It’s not to say one or the other. We need them both. But I think we spend a disproportionate amount of time in our culture looking for what is broken. And if we spent more time saying, “Where are we succeeding? Where are the things that are working, happening? What causes them to work? And are we sharing those things?” We’ll naturally start to elevate those things so more people can do them.

Yeah, absolutely. I love those topics. Just stepping back and realizing, even looking back in my own career, my own life, I’ve said that same thing. That, one, I’m also attracted to problems. And sometimes those problems, like you said, they can become those opportunities for us to grow and can be great things. So, we can turn those around. But really stepping back and saying, “This is what’s really going well,” and being able to celebrate that. The longer I live, the more I realize the world is very gray. There’s not a lot of black and white out there, which for most part, makes my first reaction is being sad. Look at all this gray that’s out there. Look at all this black that’s turned the white gray. Or not to assign color values or anything like that.

I hear you, man. I hear you.

But to realize that even though there is a lot of things that are bad in this world, there’s a lot of good, too. And there’s a lot of good things we can appreciate. So, I like that.

I’d question the premise and just in general on we don’t even know what’s good and what’s bad. And I don’t think you can create a positive thing without also creating an opportunity for something to not go how you wanted it to go. So, moral of the story is I think the world is ambiguous. And I think that’s what makes it interesting. Let’s spend time talking about what we appreciate, not because it necessarily just because it makes us feel good, though that is a big benefit. But because it helps give people a playbook for what works and they can execute that playbook.

All right. Well, close us out, Max. Let’s do this last one. Bring brightness to the room is the one that you close with, which I think is another positive thing to leave people with. So, what was the inspiration for you to bring that in? Why did that kind of say, “We have to have this one in the book. It’s got to be there”?

So, bring brightness to the room. I closed the book with that chapter because it reinforces the main idea of you are contagious. And it focuses on you being contagious in a space, whether it’s a physical space or a digital space. If you walk into a room, no matter what power you have in that room, and you are discouraging about whatever the topic at hand is, or your energy is low, or you say something like, “This is going to be boring, or this isn’t going to be fun,” you have an impact on the people around you. They will begin to mimic or adopt whatever it is you’re doing, no matter what your rank or role is in the room. Basically it’s just a reminder that we all carry a tremendous amount of ability to impact people. So, bringing brightness to the room is this idea of you don’t have to be the most chipper person in the world. Do not be disingenuous to your own constitution. But you can walk into a room without a smile on your face and genuinely say, “I’m looking forward to working with you all,” and it’s a beautiful thing. That’s all I’m asking anybody to do when they bring brightness to the room. And if you don’t feel that in a given day, you’re a human. Good news, you’re a human. You’re not going to be bright every day, right? And just letting the room know if you’re off on that day so that they don’t interpret it as Max being off because of something that happened in the room. I could have had something going on at home and just simply saying, “Today is just not my day. It’s nothing to do with this. I hope I’m not negatively impacting anyone here, but it’s just I’m not feeling it today.” Then you can be supported. But most of the days, you can probably come in and say, “All right. We have these 30 minutes allotted to do this thing. Let’s do it. Let’s enjoy it.” I think it’s just a helpful reminder that we’ve proven emotions are contagious. We’ve proven it again and again, and I cite a few different studies in the book. I don’t cite a lot of studies in the book, but that’s one where I cite two. And I think it’s important for people to remember that. I think we like to think that the leaders of the world or the managers of the world are responsible for the tone or the tempo of a room. They’re not. We all are.

Yeah, totally. We had Lee Daniel Kravitz on the show. He talked about social contagion and about how even thinking about bringing in someone’s “how much do you uplift the team?” should be a point on your performance management review. What’s the impact you have on other people with that?

You’re in a group, man. You’re doing something to the group. You’re either keeping it neutral. You’re bringing it to a spot where there’s less energy or a spot where there’s more energy so let’s bring more as best we can.

The other thought I had was we had Cheryl Kerrigan on the show who was talking about mental health and she said at their company they have these stickers that say “I’m not myself today.” You can just grab a sticker at the start of the day says, “I’m not feeling great. I got something going on. So, if you notice something, it’s not because of you. It’s something else.”

Whatever works, right? Just to communicate where you’re at and to let people know it’s not you. It’s beautiful.

Well, Max, where can people go to check out the book, to learn more about you?

Thanks for asking, Neil. dobetterwork.com. You can check out the book there. There’s some video material.

I like the video series, too. That’s nice.

Hey, thanks for checking that out. It was fun to make. So, I hope people enjoy and I appreciate you allowing me to come share these ideas.

Absolutely. We hope to have you back next time, too.

Anytime, Neil. Thank you.

Max Yoder is CEO and co-founder of Lessonly, the powerfully simple training software that helps millions of people learn, practice, and Do Better Work. Every day, he is grateful that he got cut from the basketball team two years in a row. His first book, Do Better Work, was published in February 2019. Max lives in Indianapolis with his wife, Jess.